Reading this book was always going to have a special meaning to me, as my wife had a stroke about two years ago. Like James and Bev, my wife and I are writing a book together about our experience. We honestly came up with the same chapter layout as them — alternative narrations.

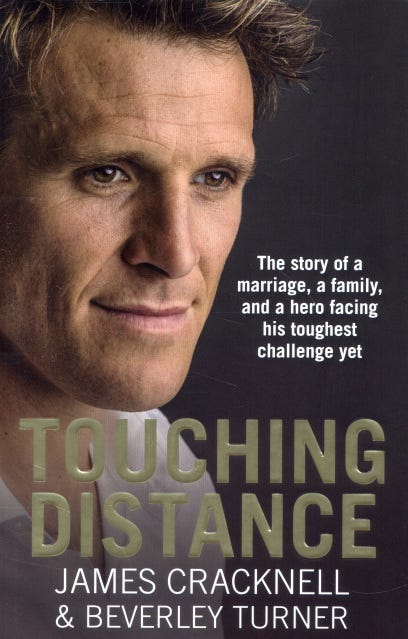

In these types of post-tragedy biographies, there are introductory chapters of the characters’ backgrounds. A get-to-know-you before the injury sequence. This is fine, but in Touching Distance, the full first half of the book is a repetitive account of Cracknell’s numerous athletic achievements. He is a very competitive individual; I get it.

At the moment of his near fatal injury, the engagement with the reader much improves, perhaps because both Bev and James are describing their separate perspectives of the events unfolding before them.

I write as a carer for a stroke survivor, so I have an empathy with Bev’s words. But I can attest that my wife would sympathise with James’s.

Bev describes learning the new vocabulary of brain injury as “taking bullets” that she would have to carry for the rest of her life. This is true.

And this unwelcomed circumstance reflects the wider dimension of changed lives. At times Bev tells James, “You’re not the man I married” and “I still miss James.” James has told the world, “I’m no longer James Cracknell.” His description of how the injury has affected his outlook is very honest and in my opinion, the most compelling part of his story.

Both mention how it’s the invisible dimension of brain injury that is more difficult to deal with. This is true, too.

Case in point was James’s description of neuropsychologist and psychiatrist tests:

“They only knew me as a patient post-accident but not the person I was or what I was capable of before the accident. So how could they impose these ceilings on my recovery based on results from generalised tests?”

We have the same complaint. In fact, neither of us were ever asked about our personalities or habits pre-injury. I still don’t understand scientifically how anyone could make predictions without examining what made a person tick before an injury.

James also recalled a qualified compliment he received after giving television commentary: “That was really good,” he was told, “especially for someone with a brain injury.” Like anyone with a disability, James said that he wants to be judged as a person, not someone with a brain injury.

With me present, a specialist once told my wife that before speaking she could tell strangers that she has had a stroke (to explain why her voice isn’t as clear). I counter-suggested that she should not, to reduce the likelihood of her being patronised. Unlike James, my wife is not famous, so it has been easier for her to present herself as herself, and not someone with a brain injury.

Both James and Bev are told that the majority of marriages fail when one has had a brain injury. It is easy to see why. Bev describes how the dynamics of a marriage of mutuality changes to one of physical and mental dependency. It’s not easy to deal with, I know. And James acknowledges this, in describing his marriage now as more of a business partnership. Both want their relationship to move back towards the centre.

Bev tells of the experience of a new friend whose marriage came undone three years after her husband’s accident. Bev asked what was the final straw? “His lack of confidence. It killed me. I couldn’t live with it.” Bev said that she knew what she meant.

Thankfully, my wife still has confidence: “If we’ve survived this, we can survive anything … it’s the ultimate challenge.”

So although Touching Distance isn’t the best written prose, like dealing with an unwanted challenge, it is worth persisting with to reach a positive conclusion and hope for a better future.